Throughout the war Māori back home played an active role on the ‘home front', serving in the Home Guard, growing food, working in essential industries and raising funds to support the men of the 28th Battalion and New Zealand's war effort. Many Māori came to the cities for the first time to work in munitions and other factories, beginning the pattern of urban migration that would accelerate after the war.

Women at work

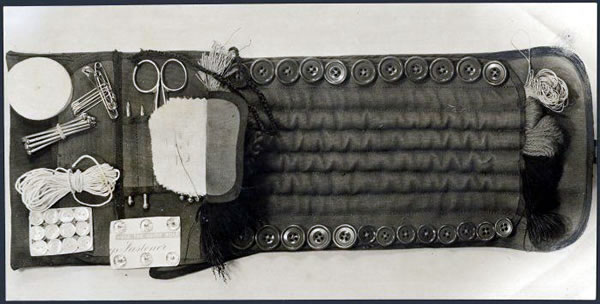

The war gave many Māori women new opportunities to enter paid employment, especially in war-related industries. Others did voluntary work, knitting balaclavas, socks, mittens, gloves and scarves, sewing flannel singlets, and baking fruit cakes and biscuits to send to the men of the 28th Battalion overseas. Women also worked tirelessly gathering and preparing seafood and non-perishable foods for the troops. Dehydration was used to preserve pipi, pūpū, karengo (edible seaweed), eel, shark, crayfish tails, kūmara and karaka berries; other food was preserved in pork fat and sealed in tins.

Māori communities also gave generously to support wartime fundraising efforts, running Queen Carnivals and other events. Tainui leader Te Puea Hērangi helped raise thousands of pounds for the Red Cross by organising dances and garden parties and selling fresh farm produce. Tainui also staged concerts for soldiers and in 1942 extended these to the American troops stationed in New Zealand.

The Maori War Effort Organisation

Identifying Māori eligible for war service was difficult because there were no Māori electoral rolls, and social security registration covered only about a quarter of the Māori workforce. Although voluntary enlistment was strong in many districts, in some areas - especially those like Waikato and Taranaki that were harshly affected by land confiscations following the 19th-century New Zealand wars - recruitment was slow.

In response, Northern Maori MP Paraire Paikea, with other Rātana-Labour MPs Eruera Tirikātene and H.T. Rātana, proposed an organisation to handle Māori recruitment and other war-related activities. Paikea won Māori support by stressing the organisation's political potential. On 3 June 1942 the government approved the establishment of the Maori War Effort Organisation (MWEO).

The country was divided into 21 zones with 315 tribal committees; one or two members from each committee joined one of 41 executive committees. Committee work was voluntary and received no government funding. In July 1942 Cabinet agreed that the principle of tribal leadership should be extended to territorial units in New Zealand and to the Home Guard.

With all tribes involved, the MWEO provided a unique opportunity to demonstrate Māori capacity for leadership and planning. Many hoped it would provide a model for post-war Māori development, but it was instead absorbed into the Department of Native Affairs.

Ngārimu's VC investiture

One of the biggest events in Māoridom during the war years was the ceremony held at Ruatōria on 6 October 1943 to honour the Battalion's Victoria Cross winner, 2nd Lieutenant Te Moananui-a-Kiwa Ngārimu. The Governor-General, Sir Cyril Newall, Prime Minister Peter Fraser, and more than 7000 Māori from all over New Zealand attended the event, which was filmed by the National Film Unit and later screened to Māori Battalion soldiers in Italy.

Ngārimu's VC citation was published in a bilingual booklet by Sir Apirana Ngata entitled The Price of Citizenship. He is commemorated in the Ngārimu VC and 28th (Māori) Battalion Memorial Scholarship Fund, which was established in 1945 to promote Māori education, language and culture.