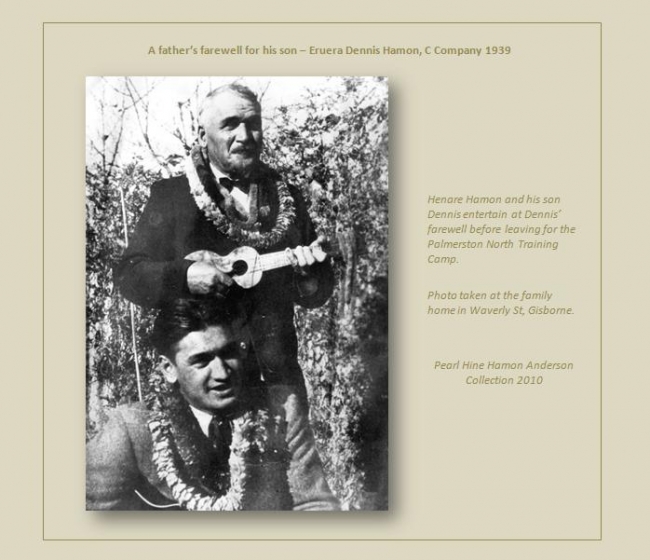

Henare Hamon (top) holds a farewell for his youngest child Eruera Dennis Hamon before he leaves for war. It is held at their home in Waverly St, Te Hapara, Gisborne. Dennis died on the 30 November 1941 and is buried in Halfaya Sollum War Cemetery, Egypt.

Reference:

Pearl Hamon Anderson Family Collection

Comments (5)

A little background...

Submitted by TeAwhi_Manahi on Tue, 30/03/2010 - 15:59

Ukeleles, banjos and piano accordians

Submitted by TeAwhi_Manahi on Thu, 28/10/2010 - 07:13

Battalion in England

Submitted by RICHARD HENRY … on Fri, 23/04/2010 - 16:24

Tena koe Richard

Submitted by TeAwhi_Manahi on Wed, 05/05/2010 - 14:14

28MB in England

Submitted by RICHARD HENRY … on Tue, 16/11/2010 - 07:54